As a director with a film background, I’m constantly struck, while working on this project, by how differently live-action and animated films are made. Here’s the distinction as I see it:

Live-Action Film

1. Work out the performances

2. Shoot it

3. Edit

Animation

1. Edit

2. Shoot it

3. Work out the performances

This is admittedly a subjective view. After all, there are plenty of live-action directors who plan their films around the cinematography and shoehorn the actors in later. But filmmaking as I know it is about creating performances, capturing them, refining them and assembling the results for maximum impact. So I definitely find myself struggling with the topsy-turvy world of animation production.

In animation, working out the timing of shots is the first thing you do. Even before you have final characters to shoot or final sets to shoot them on, you’re expected to time your storyboards and lock down your shots. You’ve effectively edited your entire animation together before you have any footage at all. From there, you work out blocking and camera angles, and only then can you begin to work on the animated performances, carefully customized to your previously chosen camera angles, and even to your previously determined shot lengths.

Of course, there are perfectly good reasons why these two workflows differ so much. In live-action, performance is a fluid, mutable thing. If a director expects to capture the best of what the actors are capable of delivering, that director has to be willing to rethink the film’s shot plan—or even the script—based on what happens in the moments between the lines. In animation, the audio track that drives an animated character’s performance is recorded and timed long before an animator even sits down to start working. Moreover, while it’s considered perfectly reasonable to shoot twelve takes of an actor’s performance and use only one, it’s a tremendous waste of resources for an animator to spend time animating anything that ends up on the cutting-room floor.

The resulting gap between the two approaches is substantial, and there’s no easy way to get the best of both worlds. The solution I’ve put together on this project is a hybrid approach that runs like this:

Live-Action-Style Animation

1. Storyboards / Animatics

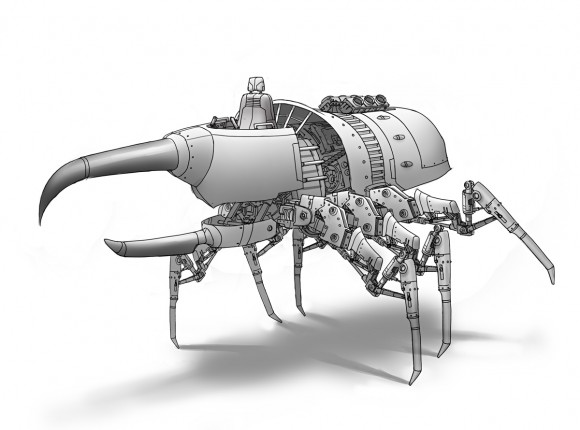

2. Rough animation using low-res proxies (pre-visualization)

3. Edit

4. Performance (final animation)

It’s not the most efficient system in the world, as it effectively requires you to animate the film twice, once before the cut and once after. Even then, it’s less than ideal—most of the acting is still added after the timing is already locked down, which means there’s not much room to shape the flow of the film around the performances. But it’s the best method I’ve been able to come up with, given my preferred way of directing and the constraints of working with an entirely internet-based team.