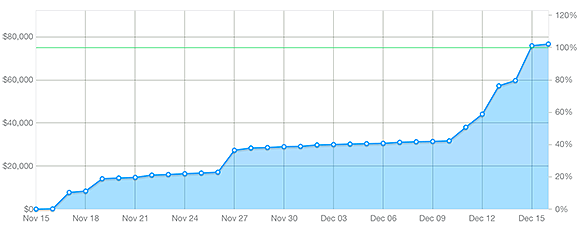

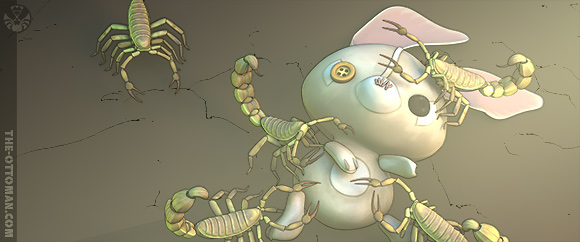

It’s been about six weeks since “The Ottoman – animated short film” successfully raised $76,700 during its 30-day campaign on Kickstarter. This was Luckbat Studio’s first-ever attempt at fundraising, and although we succeeded in reaching our goal, we also learned some surprising lessons along the way.

The Ottoman is a somewhat atypical production compared with most of the other projects listed in Kickstarter’s Film category. For one thing, despite not being a commercial studio, we have a much larger team than most no-budget independents. We’re also not adapting or remaking an existing property, which means our film has no pre-existing fan base.

Thus, the reasoning we’re outlining below may or may not apply to other aspiring crowdfunders out there.

It’s not about how much your project needs. It’s about how much people think it’s worth.

Phrased another way: make sure you do your homework.

Kickstarter’s all-or-nothing fundraising model is designed to keep campaign creators honest. If a project’s backers get the impression that its ambitions are wildly out of sync with its goals, they’ ll steer clear. But as critical as it is to make a sober assessment of what a realistic budget for your project looks like, there’s another, even-more-important assessment that a creator needs to make, and it’s a lot more sobering: how much money everyone thinks you and your project deserve.

There’s no getting around this. You can have all the passion in the world for your project, but if the average joe feels your graphic novel, or album, or game, is entitled to “ten grand at most,” then there’s a good chance that amount is where your campaign is going to plateau. No, it’s not fair. And it seems counterintuitive, since there are a near-infinite number of potential backers out there. But crowdfunding lives or dies on the consensus of crowds.

Before you launch your campaign, make sure you ask a bunch of people (not just your friends and relatives) how much they think your project deserves. And if that number is way off from your planned budget, you might want to step back and re-think your strategy.

Your goals are not Kickstarter’s goals.

Since Kickstarter’s business model is based on taking a cut of all successful campaigns, it’s tempting for a campaign creator to assume that the company is behind you every step of the way, working tirelessly to maximize your chances of success. And it is. To an extent.

But it’s important to keep in mind that Kickstarter is also running a campaign, of sorts. They’ re trying to become the biggest, most popular crowdfunding company out there. And that makes them strongly motivated to showcase those campaigns that make them look popular and successful. Would your campaign get a boost from being featured on the main Kickstarter page? Almost certainly. Would Kickstarter get a boost (of goodwill, of credibility, of money) from featuring you? If not, well…

Remember, when a campaign fails, Kickstarter gets nothing. There are a limited number of slots on the website, and a limited number of hours in a day, and Kickstarter is going to devote its time and energy to supporting those campaigns that are headed for the biggest payoff. If your campaign is still firing on all cylinders, that might be you. But if your fundraising has hit a wall in its second week, and you find yourself praying for a jolt from Kickstarter’s publicity engine, the thing is, there are a lot of competing campaigns that just hit 300% of their goal. And those ones are guaranteed to make Kickstarter happy.

The perception of success might be more valuable than actual success.

Hopefully by now, everyone in the Kickstarter community is aware that, if a campaign fails to reach its goal, it gets no money and the backers aren’t charged anything. Financially, it’s extremely low-risk. But that doesn’t matter. Backers will always behave as though their pledge is a suitcase full of cash. Time and time again it’s been shown that campaigns experience a big spike in pledges after their goal has been reached. Even though their money is never at risk, it’s as though the backers are still trying to avoid the risk of disappointment.

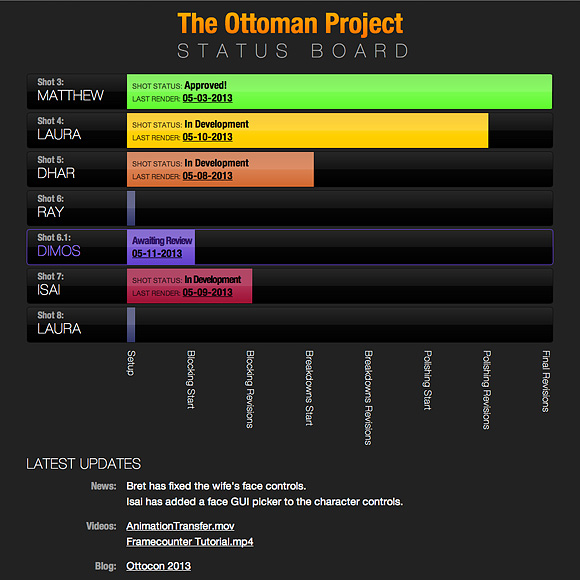

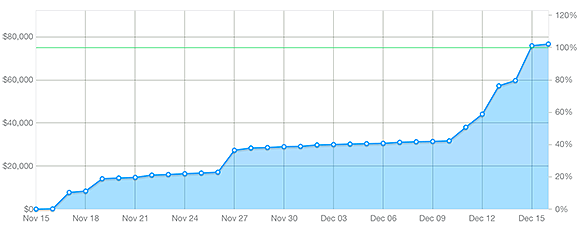

So how does this insight help a campaign’s chances of success? Consider the “Ottoman” campaign, which squeaked past its $75,000 goal at the last second, thanks to a generous matching-funds offer from Maxon Computer. We took almost four weeks just to break past the 50% mark, which for most campaigns would be fatal. We received minimal media coverage, no promotional help from Kickstarter, and never went viral, judging from our total backer count, which was less than 300.

Our goal was set at $75,000 because that’s what we calculated we needed to pay the animation team a fair wage. However, consider an alternate scenario: imagine if we’d set our goal at $33,000. We potentially would’ve hit that amount during week three, at which point those backers who’ d been on the fence start reaching for their wallets. The Kickstarter algorithm, noting that the campaign has passed 100%, lists the project up on the “Popular Campaigns” page. At that stage, with the project guaranteed to get made, press coverage becomes a lot easier to attract, and the hype begins to kick in.

Or maybe none of those things happen, we stall at $45,000, the campaign “succeeds” despite having raised little more than half of what we calculated we needed, and the project momentum is crippled. It’s a hell of a gamble.

Kickstarter is a machine that converts hype into money.

It sounds like we’re advocating deliberately low-balling your own needs to create an exaggerated impression of your success. But that’s not what we’re getting at. We’re saying that backers are extremely risk-averse, and are only willing to collectively pledge up to the amount that your project feels like it’s worth. Whatever that amount is, you need to figure it out, because that’s the number you should be setting your goal at. If you really need double that number to reach your budgetary goals, you’ ll have to make up the rest with shameless self-promotion.